Introduction

Materials and methods

Study Background

Literature search aimed to franchise operation system and industrial accidents cases

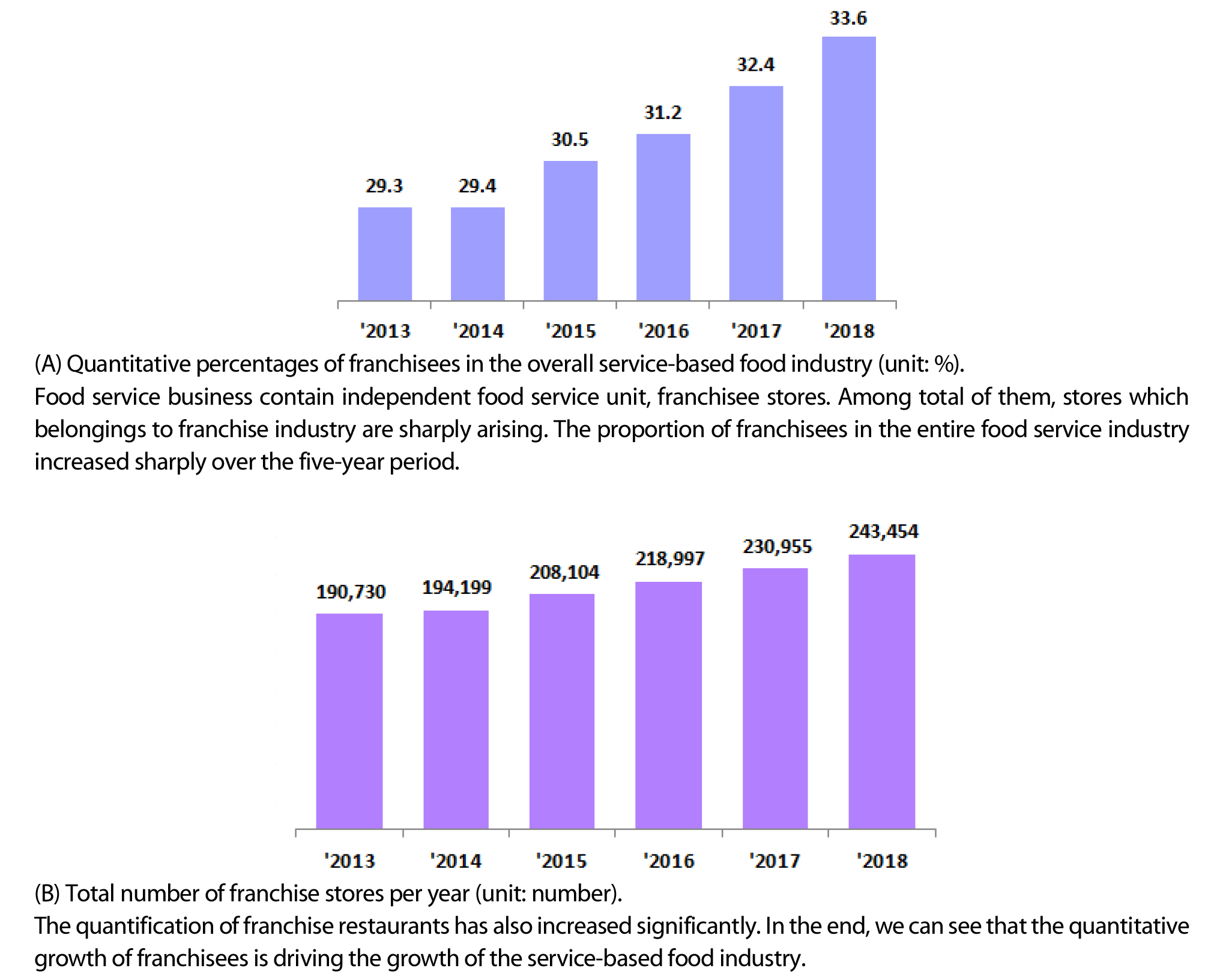

Necessity of optimized food safety management system: Franchise industry trends in Korea

Results and Discussion

Mutually inseparable characteristic: Franchise operation system and their food safety

Should be focused on collective natures of franchise

Multilateral cooperation

Identification of hazard factors derived from operating character

Introduction

The food industrial structure of major East Asian countries, including Korea, is rapidly changing owing to sharp development of service-based (tertiary) food industry. Due to such changes, we are even witnessing the emergence of the fourth industrial revolution. This trend also applies to the Korean food industry, as well, where the growth rate of service-based food industry is rapid to respond quickly and flexibly to customers’ needs, which are diversifying swiftly compared to previous years (Kwon, 2014; Park et al., 2018b). Consequently, restaurant franchise brands or franchisees based on types of food service businesses in Korea are increased rapidly (Baek and Seo, 2007; Shim and Chong, 2013; Son et al., 2012; Song, 2013). Due to its efficiency in providing flexible customer service, diversified franchise is currently driving the food industry (Park et al., 2018b).

Further, consumers’ interest in food safety issues, such as the occurrence of foodborne infectious diseasesis increasing, which inevitably forms a key issue in the food safety management field (Ahn et al., 2010; Choi and Lee, 2011). However, despite the recent trend of restaurant franchises are in rapid growth, industry or governmental experts opine that only a few food corporations developed systemic internal food safety guideline suit the operational characteristics of their restaurant franchise system.

Earlier, it was widely believed that a restaurant franchise’s food safety management is directly related to various aspects of the franchise’s own management (operation) system (Khan, 1991; Park et al., 2015; Van der Wagen and Goonetilleke, 2015). Therefore, a complemented forms of corporation’s internal food safety management guidelines reflecting operating characteristics is required, since the impact of food accidents occurred in restaurant franchises brands operating in a collective form based on service/quality homogeneity is significantly higher than that of problems issues in independent restaurant stores (Yoon and Huh, 2002).

Therefore, this study discusses relevant earlier fundamental studies about franchise operation system, and performs the following: It depicts the industrial background necessitating the establishment of franchise corporation specific internal guidelines. Based on the operational studies aimed to food franchise or their safety, it proposes some prerequisites for establishing or evolving internal-guidelines for restaurant franchises and emphasizing importance of ensuring multilateral cooperation. Furthermore, we also provided the basis for importance of such prerequisites by analyzing what went wrong in terms of their unique operating system, targeting several represent accidents officially reported that have recently become a serious social problem in the rapidly developing franchise brands. The urgency and need for such directionalities could be supported from statistical analysis of franchise industry trends implemented in this study.

Materials and methods

Study Background

The Korean domestic restaurant franchise brands (business) started in the early 1980s and, since then, it has grown significantly. In the early 2000s, domestic franchisors started expanding globally (Song, 2013). Historically, regarding mass production–based secondary industry characteristics (food manufacturing), some of the conglomerate food companies (or their brands) and leading trends encouraged the quantitative growth of the food manufacturing industry. Capitalism and the consequent securing of infrastructure enabled mass production, which generated significant profit. However, the food service industry, which operates on small FSE stores, was evaluated as negatively affecting profit generation. To overcome such limitations, the restaurant franchise industry comprising various brands developed over the years (Aliouche and Schlentrich, 2011; Gary and Rasheed, 2003; Gills and Castrogiovanni, 2012). Based on the homogenized services provided by numerous franchisees distributed countrywide, quality and differentiation of services can be achieved, customers’ diverse needs or emotions can be met, and significant profit generation can be realized through collective operation (Yoon and Huh, 2002). In addition, some of the largest capital is concentrated on the investment of many of their restaurant franchise brands, preparation of any profit decline in their mass production–based food manufacturing businesses (Kim, 1998; Lee and Lee, 2010). These franchise brands are often strengthening nation’s image by entering overseas markets (Fig. 1), since they are characterized by development based on flexible customer-oriented services (Park et al., 2018b; Yu, 2007). As a result, Korean food brands positively affect global market advancement of non-food businesses, for example, easing excessive administrative regulations of foreign nations and making it easier for other Korean companies to enter the overseas market (Park et al., 2018b).

Fig. 1.

Various types of franchise businesses in Korea: Examples of a master franchise industry.

Local food or nonfood service based commercial corporations in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, operate unit master franchise stores, such as (A) the LOTTERIA (a chain of fast-food restaurants based in the LOTTE Global Restaurant Service, a business group of the LOTTE Group in East Asia that expanded out from Korea), (B) the Tous Les Jours (a Korean bakery franchise owned by CJ Foodville, a business group of the CJ Group in Korea), (C) the Sulbing (a dessert cafe chain based in the Republic of Korea), and (D) the Kyochon (one of the largest fried chicken restaurants in the Republic of Korea).

Further, food companies with huge capital and extensive distribution networks use developed tertiary service industries to trigger the fourth industrial revolution by utilizing existing location-based services, including the geographic information system (GIS) platform and Internet of things (IoT) technologies. Further, the third industry based on customer-oriented services is considered the basis of the fourth industrial revolution. However, there are limitations to maintaining such a delicate customer orientation in traditional food manufacturing industries. Therefore, it is estimated that many food companies will continue to heavily invest in their service-based food industries. Contrarily, these industrial changes are expected to increase food safety issues faced by restaurant franchisee brands (Park, Kim, and others 2018b).

Securing food safety is an issue of utmost importance for protecting national health and consumer rights and, with an increase in public awareness regarding consumers’ rights in Korea, interest in food safety and claims has increased (Ahn et al., 2010; Choi and Lee, 2011; Kim and Kim, 1997; Lee et al., 2014). It was further shown that while Korea’s service-based industry may have a positive impact on its global image, some Korean brands encountered the opposite situation when they were exposed as being responsible for food poisoning incidents: for example, in an food poisoning case at the fast-food franchise brand ‘L’ in HôChi Minh, Vietnam, in 2016 (Vietnamnet, 2016; Saigoneer, 2016). In addition, with the increase in complexity of Korea’s socioeconomic structure, incidents of food safety management failure in the service-based industry caused a slowdown in the entire related food industry (Park et al., 2017a). The occurrence of food poisoning may cause an economic downturn in the industry or the entire tourist region. Therefore, it is very important that food corporation’s well established internal food safety guidelines optimized for the character of franchise operation system should be implemented in a timely manner. However, it is general notions that existing few internal food safety guidelines for franchise corporation are developed by reflecting traditional food manufacturing businesses which have distinctly different operating characters and manufacturing environment. Therefore, this study considered relevant studies on the unique characteristics of restaurant franchise operation.

Literature search aimed to franchise operation system and industrial accidents cases

In general, it is argued that franchise operating systems are closely related in managing their food safety. But this is only an empirical view within the industry. In order to prove this, we looked for and considered the papers that were interpreted in relation to the franchise operating system among food safety studies for franchises. For such purpose, we conducted a literature search in PubMed and Korea Science (a reference linking platform for Korean science and technology journals) using the keywords “restaurant franchise,” “food service,” “food service business,” and “restaurant” to identify published reports on Korean restaurant franchises. Second, we analyzed the abstract or introduction of the collected primary studies to identify the ones focusing on food safety issues related to operation system. We selected only those studies clearly defining their target as restaurant franchises (keywords typing results was listed: Yoon and Huh, 2002; Park et al., 2015; Park et al., 2018b).

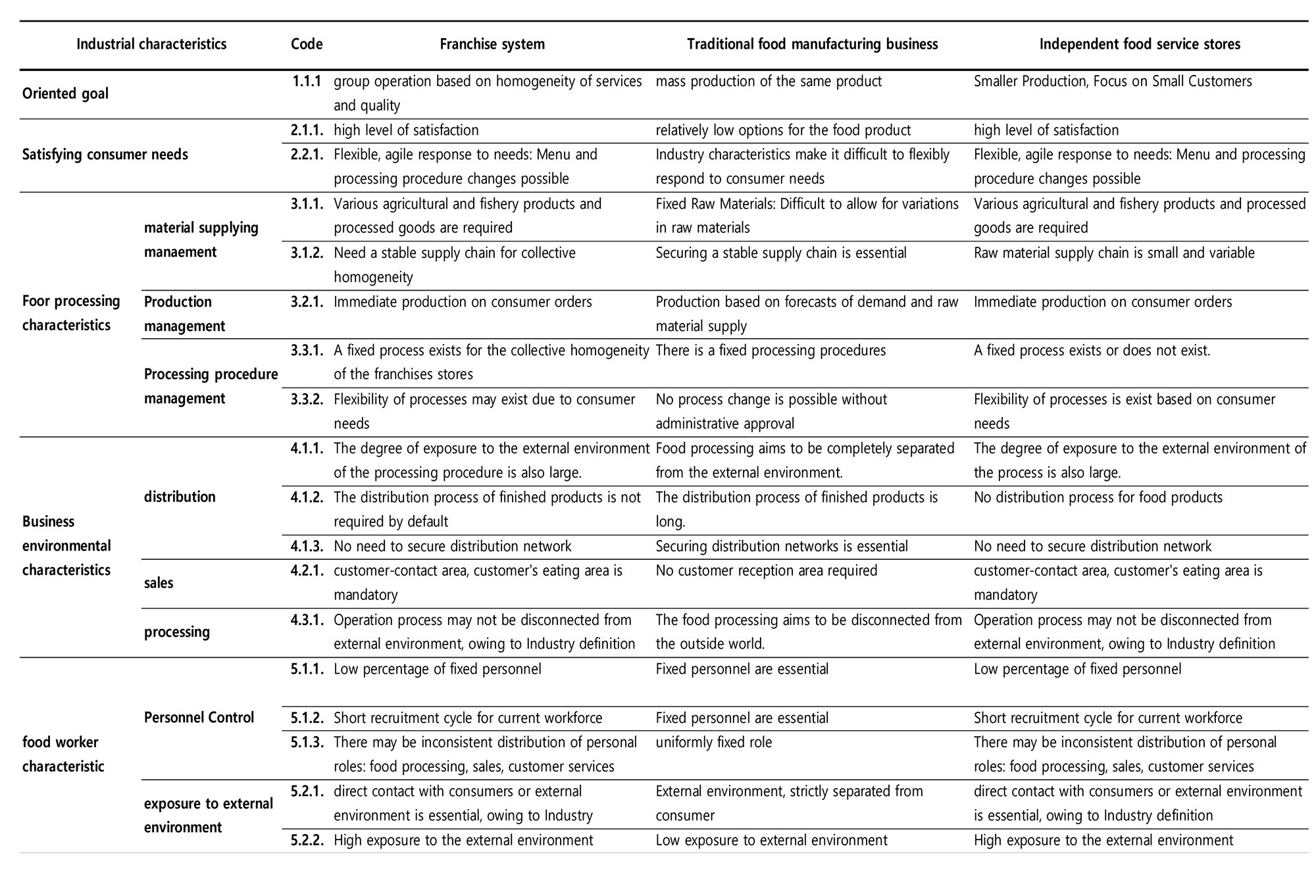

Meanwhile, they argued that most components of the franchised operating system had a direct and indirect effect on food safety management, and then analyzed a number of the literature that considered the franchised operating system in principle to identify what are the essential characteristics of the franchised operating system they refer to (keywords typing result was listed: Aliouche and Schlentrich, 2011; Gills and Castrogiovanni, 2012; Khan, 1991; Shim and Chong, 2013; Son et al., 2012; Stern and Ansary, 1998; Van der Wagen and Goonetilleke, 2015; Veronica, 2012). Ultimately, the differences in operating systems between these modern franchises and traditional food industry group also led to the effect on their working environment and food processing procedures. Elicitation of prior research and deduction of the Table 2 was were carried out by third-party food safety auditors, with professional experiences, third parties to ensure objectivity and expertise (Ollinger, Moore, and Chandran, 2004; Viator, Muth, Brophy, and Noyes, 2017). Definitive criteria in Table 2 were established based on critical discussion and peer review: panel was constituted of three professionals 1) each panel published at least six or more international or domestic journals for food safety management (This information has not been indicated by reference to avoid self-citation). They also have experience at least 6 years in conducting third party audit and professional food safety educations and developing food safety management system (FSMS) establishment aimed to both domestic and foreign franchise brands located in Korea, and Korean franchises that have advanced Asian nations. Meanwhile, we also provided the basis for importance of such prerequisites by analyzing what went wrong in characters of their unique operating system, targeting several representative food safety accidents that have recently become a serious social problem in the rapidly developing franchise brands. Cases were collected in the parliamentary report of the Republic of Korea between recent years of 2013-2019.

Necessity of optimized food safety management system: Franchise industry trends in Korea

One of purposes of this study is to suggest the establishment of a franchise-specific food safety management system. Despite the very rapid quantitative and qualitative growth of the Korean food franchise industry, food safety accidents under the incomplete establishment of food safety management systems in the franchise industry will result in the deterioration of industrial development and economic damage. Therefore, it will be possible to grasp the urgency of research and the importance of appropriate policy setting by identifying the status of franchise development. The management characteristics of the franchise are very different from that of the manufacturing industry, and the direction of the change in the franchise industry structure is critical to social change. Therefore, franchise trends were analyzed through this study by referring to the database disclosed on the Korean National Statistical Services (E-Nara Index: https://www.index.go.kr and https://www.Narastat.go.kr). The type of franchise business is applied not only to the food industry but also to various industrial groups, so only the data applied to the food industry group was re-extracted. The groups to which franchise business types are applied were the instant sales manufacturing industry and the food service industry. In the case of instant sales manufacturing industries, the following types of businesses were classified as operators prescribed by the Food Sanitation Act (MFDS, 2018) of the Republic of Korea: Industries that do not need to provide room for consumers to eat, such as side dishes, lunch boxes, bakeries, confectionery and fast food. In the case of the food service businesses, it is basically providing a dining space for consumers such as Korean, Chinese, Japanese or fusion dining, and fast food. The trend of change was used to interpret how highly the unique operating characteristics of the franchise are appearing in Korean society, because such unique management characteristics can be used to determine the necessity and urgency of food safety management guidelines optimized for the franchise. It was supposed that the stronger the franchise- specific operational characteristics, the greater the risk from the franchise’s own failure to manage food safety. To prove this, this study seeks to identify the link between the operating characteristics of the franchise and the typical case of food safety management failures officially reported in Korea. Through this, it will present the direction of franchise-specific internal guidelines.

Results and Discussion

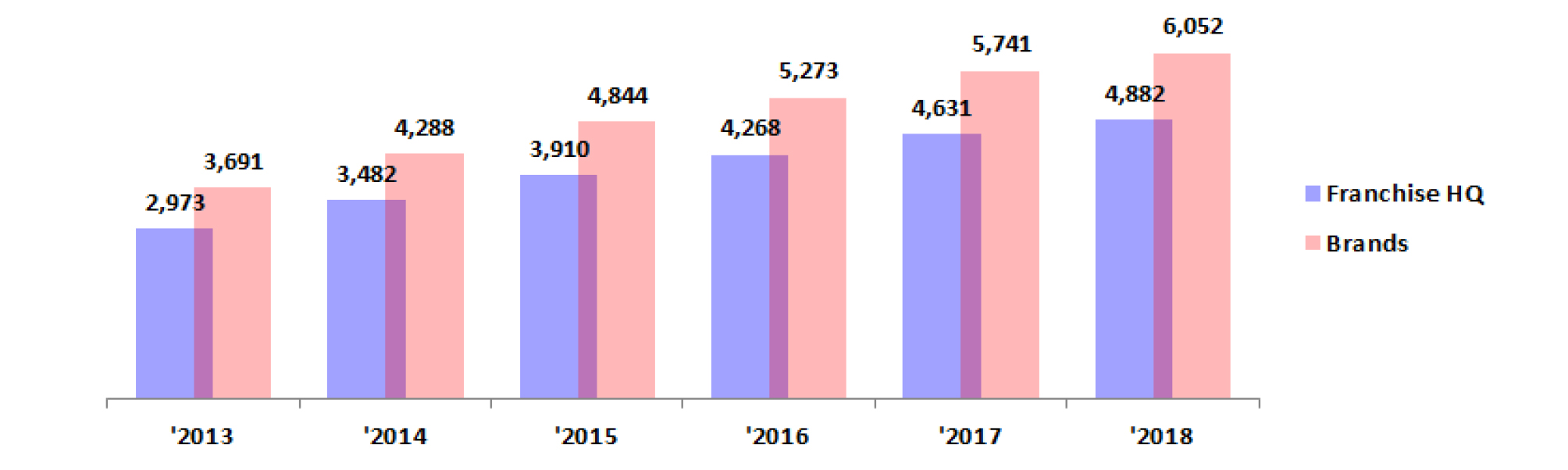

According to the statistical analysis, the proportion of franchisees excluding the distribution industry among the total service-based food industry increased steadily and rapidly, increasing 14.6% over the five-year period. (Fig. 2(A)). The absolute number of franchisee unit stores has also risen 27.6 percent over the past five years, and indicating a steady and rapidly increasing trend (Fig. 2(B)). Specifically, the franchising HQ saw a 12.84% increase over the past five years, a 12.79% increase in brand numbers. Despite the severe fluctuations in economic conditions, it has been found that there has never been a year of decline (Table 1). Totally, total food franchise count up sales account for 6.9% of Korea’s nominal GDP and employment for 4.5% of the economically active population. This means that studies on internal food safety standards unique to franchises should begin in earnest. The development of South Korea’s service-based food industry group is led by franchise brands, which have differentiated operating systems, operating entities, manufacturing processes and manufacturing environments from traditional food processing and manufacturing industrial group. However, in traditional food processing and manufacturing industries, all of such factors have been directly or indirectly related to the establishment of food safety management systems (systems of hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP), international organization for standardization (ISO) etc.) thus those factor are reflected in the establishment or amendment of FSMS. Since such factors have distinct characteristics between the processing and manufacturing industry and franchises systems, it shall be approached in a different form than the corporation’s internal food safety guide lines used for manufacturing when establishing a FSMS for franchises. The franchisee is basically part of the service-based food industry and therefore has a working environment similar with a single food service store establishment. However, franchises have a collective operating system, and the actors involved in the operation are very complex (Park et al., 2015). Therefore, it should be approached in a different way than the traditional food safety management measures targeted at a single (independent) food service store. Such discrimination from the existing food industry will have to be reflected in the development or evolution of the franchise brand’s own food safety management guidelines.

Table 1.

Changes in the industrial scales of Korean restaurant franchises in the last 6 years

Meanwhile, the need for the preparation of the franchise or franchise brand’s own food safety management standards can also be derived from the brand’s conceptual relationship with the franchise. Brand is different from the concept of franchise, and the correlation between franchise and brand concept is as follows: Franchise is a kind of food company registered as a franchise business based on its own operating system, and is operated in a contractual relationship between the "Franchise headquarters" and the "Franchisee stores" as defined in the Act on the Operation of Franchise Business (the Fair Transactions in Franchise Business Act (MOTIE 2016, 2018b). Unlike the original concept of franchisees, however, ‘brand’ can exist as a trademark value regardless of whether it is legally permitted or not. From the perspective of a franchise (franchise HQs), a franchise can run one or multiple brands, and each brand aims for its original identity based on its own service and quality strategy. The reason for having multiple brands is to secure a diverse customer base through franchises belonging to different brands with different identities, thereby increasing their market share. In addition, from the perspective of franchisee stores, a single franchise is established in the business permission under the Food Sanitation Act, but multiple brands can be claimed. What is shown to the customer through the franchisee stores is close to the concept of the brand, and it is not known which franchise headquarters it belongs to. The franchise headquarters is obliged to manage the food safety of entire franchisee stores by establishing standards for the food safety management (article 100 of the Food Sanitation Act, article 17 of the Act on origin labeling of agricultural and fishery products (MAFRA and MOF 2017; MFDS, 2018), However, if differentiated services are provided by each brand, this can generally affect the method and difficulty of its own food safety management system. For example, coffee brands and bakery brands have different processes, facilities, working environment, and service environment, so internal food safety management standards should be differentiated accordingly. It is not legally required to establish discriminatory food safety management standards for operating multiple brands. Therefore, the importance of developing optimized food safety management standards should be emphasized. Generally, internal food safety management standards are manualized or sanitation standard operating procedure (SSOPs) are managed as media, and these standards are designed by borrowing global guidelines such as ISO, BRC and CFA (AIB International, 2014; BRC 2011) based on their national laws. However, for low-profile or small- and medium-sized franchises, their own guidelines are not systematic and remain at a rudimentary level (Park et al., 2015). Or, it is often not optimized for franchise or brand management environments because it is borrowed from existing manufacturing and processing standards (Park et al., 2018b).

Mutually inseparable characteristic: Franchise operation system and their food safety

For the first time in Korea, Park and others (2015) compared and analyzed the management status of food origin indication between restaurant franchises brands and individual FSE stores and found clear differences (Section 3.2). These differences were attributed to the franchises’ unique operating characteristics, and they indicated that elements of operating systems affect the management of food origin indications, which is important issue pertaining to food safety in Korea. All the elements of franchise operating systems (R&D, education, supervision, logistics, and merchandising) were found to be directly related to food origin management (Blay-Palmer, 2016; Jung and Ku, 2015; Park et al., 2015; Son et al., 2012; Song, 2013; Stern and Ansary, 1998; Yoon and Huh, 2002). These systems were proved to negatively affect food safety management and food origin indication management when incorrectly established.

Important accidents cases related with such factors have been emerging nowadays: Several franchisees in Daejeon and the North Gyeongsang Province in the Korea Republic were simultaneously cracked down for unintentionally mislabeling food origin. The restaurant franchisee’s headquarters (HQ) had distributed exclusive food materials (food material supplies common to franchisee stores within a certain range designated by the franchise HQ to unify taste and quality). New food menus can be developed through R&D by the HQs, or major food materials can be found and their food origin information be reported to franchisee stores to maintain uniform quality and service across these stores (related with clause 3.1.2 in Table 2). However, since they depend on consignment

Table 2.

Differences in franchise brand operating characteristics: food processing procedures and environment (and their relation to food safety management in real industrial sites)

production of the major food materials used by them (related with clause 3.1.2 in Table 2), they did not recognize the change in the geographical origin of raw materials of the suppliers and distributed them to their franchisee stores. The reason for this failure is that supervision, quality control, and merchandising, which constitute the operation system, were not managed organically. Further, Park reported that some brands that failed to control origin indications during monitoring (24 months) suffered bankruptcy primarily due to their incomplete franchise operating system.

In summary, the first consideration in a franchise-optimized internal guidelines for corporation is that its unique operating system should be factored in amendment or establishing franchise food safety management. In addition, if food safety problems arise due to incomplete franchise operating systems, the social impact could be much greater than that associated with independent FSE stores, due to some nature of franchises (Park et al., 2017a; Park et al., 2018b). One of such nature is: A franchise HQ operates a number of brands (related with clause 1.1.1 in Table 2). This is an economic strategy to secure a diverse customer base, which can prepare for unpredictable changes in economic conditions and recession. In terms of food safety, however, failure in the food safety guidelines of the franchising HQ could simultaneously threaten the food safety level of the entire brand. This translates into a food safety management feature derived from the franchise-specific profit-production characteristic, which runs a collective management system based on homogeneity of franchisee stores. In view of the statistical changes, the gap between the number of franchise HQ and the number of brands has been increased in recent years, meaning that a single franchise has become more inclined to run multiple brands (Fig. 3). The major difference between the HQ of the restaurant franchise and the franchise brand was 718 in 2013, but the gap increased 62.95 % to 1,170 in 2018 (Table 1, Fig. 2). In addition, the increase rate for franchise HQs is 65.211% over the past five years, and the increase rate for brands is 63.97 % (Table 1, Fig 2). Therefore, the percentage of increase in the number of franchises and brands is similar. This is interpreted as the tendency of a single company to run a number of brands has become entrenched. Therefore, it may be necessary to implement a food safety management strategy or hygiene certification system to monitor the restaurant franchise operating system elements themselves.

Fig. 3.

Variance of number of food franchise businesses (unit: number).

Franchisor (correspond to franchise headquater) and their brands are rising simultaneously. A franchise HQ could operates one or diverse brands. Such examples are well presented in Fig. 3 and 4. Ratio of franchise HQs and Brands are gradually consistent, which means that one franchise headquarters is evolving toward securing multiple brands. By securing multiple brands, the company can secure a diverse consumer class, which is analyzed to prepare for a recession and uncertainties in market conditions.

Should be focused on collective natures of franchise

Unlike traditional food manufacturing businesses, franchises have their own, unique management environments (Aliouche and Schlentrich, 2011; Gills and Castrogiovanni, 2012; Khan, 1991; Luning and Marcelis, 2006; Stern and Ansary, 1998; Yoon and Huh, 2002). Existing food manufacturing businesses attempt to certify HACCP for the production line unit owned by a plant; since the plant comprises a management unit, adequate food safety can be ensured by introducing HACCP to the relevant plant unit (Choi, 2014; Lora and Douglas, 2005) (related with clause 3.1.1-3.3.2 in Table 2). However, since restaurant franchises maintain collective homogeneity, for which the franchise HQ is responsible, the effectiveness of food safety certification introduced aimed to one individual franchisee stores is questionable. For food manufacturing businesses, HACCP or ISO assigns clear responsibilities and authority to the organizational components comprising the manufacturing business unit to ensure successful food safety management (Luning and Marcelis, 2006), since unclear or redundant responsibilities and authorities hinder systematic management (Park et al., 2018a). ISO 22000 is a standard developed by the International Organization for Standardization dealing with food safety, and international standard specifies the requirements for a FSMS that involves the following elements: interactive communication, system management, prerequisite programs, HACCP principles (Luning and Marcelis, 2006; Trienekens and Zuurbier, 2007; Varzakas, 2011; Ziggers and Trienekens, 1999).

In general, food manufacturing businesses making specific products have independent organizations, which have complete authority over the plants’ operation. In addition, the responsibilities and authorities of the members of such organizations are clearly specified. However, in food franchises, both franchisee owner and HQ are involved in the operation of unit franchisee stores, since the basic role of HQ is to provide management support for individual unit franchisees (MOTIE, 2016; Park et al., 2018a; Park et al., 2018c; ; ). This is a unique characteristic of the franchise operation system. Since the unit owner has some control over the stores under HQ’s management support, the managing role is not confined to individual unit franchisee stores alone (MOTIE, 2016).

Therefore, the second factor to be considered in restaurant franchise food safety management is that certain, strategies, or corporation’s internal food safety guidelines should not be concentrated in a unit franchisee stores - it can be a narrow view. If internal hygiene system is introduced in individual unit franchises, there will be a disparate part with the franchise brand’s own management or operating system. We have to note: Regarding the nature of restaurant franchises, relevant previous studies and Korean laws note the following: The fundamental reason for introducing franchises’ own operating system is the rise in competitiveness based on the collective homogeneity of tastes, quality, and service across all franchisees or direct stores (MOTIE, 2016; Yoon and Huh, 2002). If a franchise or brand’s own food safety management system exists, it inevitably reflects the characteristics of the franchise’s unique operating system elements (Park et al., 2015), and if an external certification system is introduced again, it will be difficult to reconcile or make normal use of the system. For example, various food hygiene certification systems have been administratively attempted for the food service industry in Korea, but there have been many cases of hygiene accidents and food poisoning in certified businesses, which may be due to heterogeneity between two operating systems. Therefore, certain administrative food safety certification aimed to operating system of the franchise headquarters may be more efficient and sustainable than introducing a food safety certification system for individual franchisee stores.

Multilateral cooperation

When analyzing prior studies, the operation style of the franchise can be divided into several typical operating types since year of 2010, including concession business and master franchise (Gills and Castrogiovanni, 2012). They are reported to have difficulty in setting up food safety management bodies due to the complexity of management entities. They seems to usually occur in the phase of advancing abroad or encroaching on the domestic market. According to a related statistical analysis in this study, 254 out of 4,880 franchise companies in Korea (5.2 %) are going overseas (data not shown). If restaurant franchises are classified as Korean, snack, Chinese, Japanese, Western, chicken, pizza, coffee drink, ice cream, fast food, liquor store, and other, the following are the areas where overseas advancement has been made: Coffee and beverage (59, 23.2%), Fried chicken (57, 22.4%), Korean food (55, 21.7%), Snacks (47, 18.5%), Japanese and Western style (31, 12.2%), Confectionary and bread (5, 1.97%). Fortunately, it is estimated that in the case of coffee and beverage brands, the standardization of food materials are well carried out and it will likely be operated in a traditional franchise operation forms- direct management or franchisee form, rather than in the form of master or concession. However, if a variety of food materials are required for food manufacturing process such as fried chicken, Korean food, snacks and food, it is likely to be in the form of master franchise systems because it may be inefficient to supply food materials them from their home country, according to analyzing previous studies, and in these case, the master franchise HQ receives only the price for its trademark (loyalty) (Veronica, 2012; Gills and Castrogiovanni, 2012). There are two main reasons for doing so. The first is that master franchise operation is emerging as an industrial group as a means of overseas advancement of franchise brands, and because of the efficient attainment of this purpose, franchise brand HQ has only the right to royalty, and menu development and raw material supply are owned by local business owners. This is to obtain food materials locally at the beginning of their advance, and to develop some menus accordingly, and to increase brand awareness first. In addition, when small and medium-sized franchises enter foreign markets, the process of developing stores may not be difficult if they enter abroad nations along with other service sectors, especially commercial facilities. However, if a brands of food corporation’s overseas expansion is successful, another brand owned by that company can easily advance based on the infrastructure it is configured with. Therefore, it is estimated that the speed of overseas expansion will be faster at a time when one HQ has a variety of brands. However, these characteristics can cause difficulties in food safety management, such as: Cho and others (2018) reported that the involvement of too many entities in the operation of restaurant franchises made systematic food safety management very difficult. The first requirement of ensuring food safety management is the establishment of managing body where numerous economic players are involved in the service-based food industry franchise operation: for example, concession business franchises (Lee and Lee, 2010) (Fig. 4), master franchise system (Park et al., 2017d; Veronica, 2012) (Fig. 4), and franchise stores in large commercial complexes (Gills and Castrogiovanni, 2012; Khan, 1991; Kim, 1998; Shim and Chong, 2013), making it unclear who should assume management responsibility. Generally, food safety is maintained very efficiently when HACCP or ISO is carried out for one complete management unit, such as a single manufacturing plant or an independent FSE store (Luning et al., 2006; Trienekens and Zuurbier, 2007; Ziggers and Trienekens, 1999). However, for restaurant franchises with complex operating entities and relationships among them, effective food safety management is realized only when various entities and their corresponding responsibilities and authorities are clearly defined. We have to note that in a major concept of the HACCP system or ISO 22000, first priority is given to the setting of clear responsibilities and authority within the food safety (or quality assurance) team (Luning et al., 2006; Trienekens and Zuurbier, 2007; Ziggers and Trienekens, 1999). Therefore, the fourth direction to successfully secure restaurant franchise–optimized internal food safety guidelines requires multilateral cooperation among the various entities involved in the operation. Today, the Korean economy is much more complicated than it was in the past and the relations among industrial players are becoming highly complex, as well. This results in various problems among industrial entities, including the tyranny of subcontractors; hence, social systems are continuously undergoing change to manage such problems (Park et al., 2017d). Although cooperation among various players in the service-based food industry can be a key aspect of food safety management, research has shown that food safety management is associated with various components of a company’s own management system. Various entities involved in a particular franchise restaurant stores can cooperatively perform food safety management; however, while supporting partner franchise food safety management, one should be careful since the process may affect the management system of the partner company. This study is meaningful since it provides scientific definitions to manage the tedious debate prevalent among various operating entities. For example, although various laws mandate the legal involvement of operators of commercial facilities in the food safety management of franchise stores operating in these facilities, there is no systematic social agreement on the extent of their involvement for securing food safety. Further, it is unclear whether only a portion of the unit stores’s compliance with food safety laws should be monitored, in the fragment mode or even in support of the improvement of the operation system’s insufficiency, which could cause inefficiencies in food safety management. The latter case can result in sensitive issues since it requires involvement in the partner food company’s operating system. Such conduct often causes controversy over infringement of managerial control of the partner company.

Therefore, the fifth direction to successfully secure restaurant franchise–specific food safety management strategies requires that the social system clearly defines the scope of responsibility of the concerned entities. Such a clear definition is expected to promote the successful application of the restaurant franchise’s own FSMS in its complex management environment.

Fig. 4.

Various types of Korean franchise businesses: Examples of concession.

Franchise brands collectively operate in the Gimpo International Airport (A), the Incheon International Airport (B), university-affiliated hospitals (C), and the Korean high-speed railroad station (D). Owing to the nature of the service industry, restaurant franchises attempt various types of businesses unlike the traditional food manufacturing industry. They are also able to have complex interactions with nonfood industry groups because of the unique nature of customer service–based industries. Therefore, inevitably, their operations involve diverse entities. In particular, in the concession industry, the nonfood industrial entities associated with franchise operation can change dramatically and do not have an entry barrier. Therefore, multiparty cooperation is required under clear management scope and authority for food safety between the operating entities. In addition, social guidelines should be developed to ensure efficient, rational, and legal multilateral cooperation.

Important cases proving such arguments are have been emerging nowadays: In the concession business (Lee and Lee 2010) (Fig. 4), a kind of the restaurant franchise business tried in large commercial facilities, such as international airports (Kim, 1998), and a state-run company having airport management authority had operate various unit franchisees of various brands in a leased form (Park et al., 2018a). Later, the state-run company was severely blamed by the national assembly of South Korea and social media regarding a franchise food safety lapse incident, which occurred due to the presence of an ambiguous managing body and the complex nature of business rights (National Assembly of South Korea, 2016). However, in practice, an airport operators has no primary responsibility in ensuring food safety, as defined by the relevant laws, whereas the franchisor and franchisee are legally primarily responsible for any food safety lapses, as defined by the Food Hygiene Act (MFDS, 2018), Food Origin Act (MAFRA and MOF, 2017), and other associated acts (MOTIE, 2016. 2018a. b. Park et al., 2015. Park et al., 2018a). Although a state-owned company with the authority to operate an airport has no legal responsibility, it may assume moral responsibility in a successful win-win situation. However, if a franchiser relies on moral responsibility alone, it can hinder the balanced growth of small and medium-sized franchises. Conversely, if the airport manager had actively intervened in the franchise’s food safety–related operating system, it could have caused a controversy over violence against subcontractors (correspond to franchisee stores or its HQ operates leased in airport). Therefore, a clear distinction between legal and moral responsibilities clarifies the responsibility and authority of the food safety management body and ensures fundamental safety management. Although the extent to which parties involved in franchise operations are responsible for food safety management may be negotiated by mutual agreement, it should be based on this review’s findings. This study provides a new perspective to such controversies within the restaurant franchise industrial environment. It provides a fundamental basis for on further coordination and development of administrative entities within the changing food industry, as well. If the social policy defined some responsibilities and authority, detailed responsibilities and rights not otherwise established could be overcome through inter-contractual relationships among diverse operating entities. In any country, the speed of development of an administrative system cannot match that of social change (Lee and Park, 2014). However, due to the nature of social policy, most national laws focus on post-management and guidance, whereas companies establish internal food safety policies focusing on advance care to meet these criteria (Park et al., 2018b; Park et al., 2018c). Therefore, restaurant franchises brands should research and develop hygiene standards (or practices) optimized for their own operating environments to fulfill their social responsibilities. Such processes may benefit from this study.

Identification of hazard factors derived from operating character

Government and industrial experts opine that restaurant franchise businesses encounter difficulties in applying the HACCP principle or other prominent systems derived from traditional food manufacturing industries, which is optimized for traditional food manufacturing lines based on the mass production of diverse products or independently operating restaurants (Park et al., 2018c). According to such opinions and previous research findings, microbiological management standards, such as cleaning or disinfection practices, should be complemented as appropriate for the unique working environment characteristics of restaurant franchises, along with maintaining the critical control point management concept. However, to date, scholarly study has revealed the differences between the working environments of manufacturing industries and franchise restaurants are few. Therefore, one of direction for securing an franchise corporation’s internal food safety guidelines optimized for restaurant franchises operation requires comparative analyses of the differences between food manufacturing environments and franchise environments, and these analyses should be followed by the proposal of management strategies that suit franchises’ unique working environments.

What is the difference between the franchise brand operating characteristics of the traditional food industry? What difference is caused by such fundamental differences in the work process and working environment? These questions are answered by panel discussion in this study, and these differences may be directly related to food safety. Although this study was the first to derive the differences between these industry groups, more elaborate research should be conducted to ensure internal food safety management guidelines for companies optimized for franchise operation.

There are food safety accident cases according to the unique operating characteristics of the franchise: incomplete operation systems of undergrowing small or middle-sized restaurant franchises depend on their supply of materials to consigned production (related to clause 3.1.1., 3.1.2 of the Table 2), methods of ensuring food material safety should be considered. Note, supply management is defined as one of the important food safety programs in most of global food safety guidelines (AIB International, British Retail Consortium, 2011; Chilled Food Association 2006).

Important cases proving such arguments are have been emerging nowadays: In 2018, a school meal scheme implemented by a brand of the parent company that was attempting to establish a new type of food franchise (concession business) in Korea was responsible for a major food poisoning incident. It was found that the consigned small franchise company’s failure to ensure food material supply control caused this serious food poisoning. More than 1,000 suspected cases of food poisoning have been reported by ingestion of Korean wheat chocolate blossom cakes. Health authorities have banned the distribution of food cakes from affiliate food supply firms. Epidemiological studies have found Salomella species, a pathogen, in feeding cakes and patients.

More seriously, more food safety studies are urgently needed to target franchise restaurants. A few studies have been done aimed to franchise food safety. Not so much research has been done on franchises’ food safety. Choi and others (2016) examined the microbiological safety of lunchboxes sold by franchisees. They conducted a survey to clarify the compliance of microbiological standards in food processing; however, they did not suggest any reason for the franchise operating system’s failure in microorganism management. Kim and others (2014) compared the microbiological `safety of meals for poorly-fed children made by several franchise brands. However, they did not provide any reason for the franchise operating system’s failure in microbiological safety management. Although microbiological assessments of the operating environments and products of food service businesses have been conducted, it is unclear whether they targeted restaurant franchises with unique characteristics. In addition, most of the domestic studies on food safety management in food companies are simple surveys or case studies of specific situations. Meanwhile, in response to changes in food poisoning patterns, several studies were conducted to present new standards applicable to the operation system of food service businesses, including restaurant franchises. Presenting a new standard for controlling food worker–mediated gastrointestinal infectious diseases by conducting several studies (Park et al., 2018b). It developed new standards as a clause of SSOP, since SSOP can ensure some food operators’ hygiene standards very easily and efficiently (Chaifetz and Chapman 2015; Cusato et al., 2013; Kussaga et al., 2014; Viator et al., 2017).