서 론

재료 및 방법

실험 재료 및 발아

분석 샘플 준비

Phytase의 효소역가 분석

Phytase의 역가 비교 및 효소 특성

통계분석

결과 및 고찰

발아 곡류의 phytase 역가 비교

보리의 발아 기간 동안 phytase의 변화

발아 보리 phytase의 특성

서 론

Phytase(myo-inositol hexaphosphate hydrolase)는 동물뿐만 아니라 인간의 영양 분야에서 광범위하게 활용되고 있으며, phytate를 myo-inositol 및 무기태 인산염으로 가수분해를 촉매 하는 효소이다(Haefner et al., 2005; Mittal et al., 2013). Phytate, myo-inositol(1,2,3,4,5,6) hexakisphosphate는 완숙한 곡류 및 콩류에서 인의 주요 저장 형태이다(Cosgrove, 1966; Haefner et al., 2005; Kumar et al., 2010). 유기태 인, phytate은 식물성 사료원료에 총 인의 60~90%가 phytate phosphorus 형태로 결합되어 높은 수준으로 함유되어 있다(Raboy, 2003; Wu et al., 2009).

Phytate은 Ca2+,Mg2+,Zn2+,Cu2+,Fe2+ 및 Mn2+와 같은 2가 양이온과 잘 결합하여 폴리머 킬레이트를 형성하는 대표적 물질이다(Harland and Oberleas, 1999). Phytate는 P 및 다른 미네랄의 용해도, 소화 및 흡수에 부정적 영향을 주어 사료에서 Zn, Fe, Ca, Mg, Mn 및 Cu의 생체이용률을 상당히 제한하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Sebastian et al., 1998; Harland and Oberleas, 1999; Wu et al., 2009; Vashishth et al., 2017). 따라서 phytate 분자와 이에 결합된 영양소는 phytase에 의한 효소 분해가 없이 소화관에서 소화 및 흡수가 될 수 없다.

단위동물인 돼지와 가금은 소화 장기에서 phytate을 분해 할 수 있는 효소 분비가 충분하지 않기 때문에 이용이 되지 못한다(Cowieson et al., 2016; Dersjant-Li et al., 2015). 따라서 흡수되지 않은 phytate는 배설되어 환경 인산염 오염에 원인이 되기도 한다(Humer et al., 2015). 가축 사육 증가와 함께 지속된 분뇨의 토양 살포는 식물 요구량을 초과하고, 토양에 인산염 축적을 초래하고 있다(CAST, 2002). 또한 이것은 지표수의 부영양화로 이어질 수 있으며 인산염이 지하수로 장기간 침출될 것으로 예측된다(Furrer and Stauffer, 1987). 따라서 양계, 돼지 및 어류 사료에 phytase의 활용은 인, 미네랄, 아미노산 및 에너지의 이용성을 향상시킬 뿐만 아니라 기축 생산을 위한 무기태 인산염의 추가 공급을 줄이고, 가축분뇨에서 인산염 배출을 줄이기 때문에 환경 친화적 물질이라 할 수 있다(Nahm, 2002; Rao et al., 2009).

Phytase는 자연계에 널리 퍼져 있다. 예를 들면 송아지, 새, 파충류 및 어류의 혈액에서 보고되고 있을 뿐만 아니라(McCollum and Hart, 1908; Rapoport et al., 1941; Gibson, 1987), 옥수수, 벼, 밀 및 대두 등과 같은 식물에서도 발견된다(Hayakawa et al., 1989; Hamada, 1996; Huebel and Beck, 1996; Nakano et al., 1999). 그러나 호밀, 밀 및 보리와 같은 일부 곡물에는 phytase가 비교적 높지만 옥수수 및 유지 종자 분말과 같은 사료 원료에는 거의 또는 전혀 포함되어 있지 않다(Eeckhout and De Paepe, 1994; Gupta et al., 2015; Vashishth et al., 2017; Bouajila et al., 2020). Phytase의 효소 활성이 풍부한 식물성 사료 곡물의 급여는 동물의 소하 장기에서 인의 생물학적 이용을 향상시키기 때문에 추가적 무기 인 보충제와 생산 비용을 줄일 수 있을 것이다.

종자 발아 중에 phytase는 자연적으로 활성화되며, 이러한 발아 공정을 응용하여 곡물의 효소 역가를 증가시킬 수 있다(Sung et al., 2005; Gupta et al., 2015). 보리는 유기태 인의 함량이 높고 발아 과정을 통하여 생성되는 phytase가 비교적 높은 것으로 보고되고 있다(Sung et al., 2005; Bouajila et al., 2020). 또한 국내에서도 발아보리는 식혜 및 맥주 제조공정에 사용되어 대량 생산이 가능하다. 따라서 본 연구는 phytase가 풍부히 활성화한 곡물사료 원료로서 발아 보리를 생산하기 위한 연구로 발아보리와 다른 곡류와의 phytase 역가를 비교하였고, 보리가 발아하는 동안 phytase의 효소 역가 변화 및 발아 보리 phytase의 효소 활성 특성에 대하여 연구하였다.

재료 및 방법

실험 재료 및 발아

발아 실험을 위하여 사용한 씨앗은 지역 판매점을 통하여 구매하였으며, 발아는 Konietzny et al.(1995)과 Greiner et al.(1998)의 방법을 활용하여 실시하였다. 보리(Hordeum vulgare L. cv. Olbori)는 표면의 계면장력을 감소시키기 위하여 0.1% Tween 80에 5분간 침지 후 0.75% H2O2에 1분간 소독하였다. 그리고 멸균 수로 행군 후에 증류수에 16시간동안 4°C에서 침지하여 발아 샘플을 준비하였다. 준비된 보리는 위생 거즈 2겹 위에서 수분을 유지하며 25°C의 어두운 환경에서 5일간 발아를 진행하였다.

분석 샘플 준비

효소 역가 및 단백질 분석을 위하여 발아기간 동안 24시간 간격으로 샘플을 채취하여 실온에서 건조 하였으며, 건조된 발아 보리는 주방용 분쇄기(Hoodmixer, Hanil, Korea)를 이용하여 분말을 준비하였다. 효소액 추출은 Azeke et al.(2011) 및 Ma et al.(2015)의 방법을 응용하여 준비된 분쇄된 샘플(1 g)은 10 mL의 0.1 M acetate buffer와 혼합하여 4°C에서 16시간동안 진통 추출기(Thermo Mixer, KBT, Korea)를 사용하여 추출 하였다. 순수한 추출액은 8,000 g에서 30분 원심분리를 실시한 후 상등액을 취하여 준비하였다.

Phytase의 효소역가 분석

보리의 발아기간 동안 phytase 발현을 스크린하기 위하여 Agar Plate Staining 방법을 실시하였다. Phytate agar plate는 250 mL의 1.8% Agar에 6 mL의 10% Na-phytate, 1mL의 myo-inositol 및 2 mL의 10% CaCl2를 무균 상태에서 혼합하여 agar plate로 준비한다. 준비된 phytate agar plate에 효소 샘플을 채울 수 있은 정도이 홀을 도려내고, 준비된 효소 추출물을 채우고 37°C에서 16시간 동안 반응을 일으킨다. 효소 반응 염색은 20% cobalt chloride로 10분간의 반응 시간을 부여하고, 6.25% ammonium molybdate와 0.45% ammonium vanadate 혼합용액을 15-20분 동안 반응을 하여 효소작용 부위가 주변보다 연한색을 띄는 것을 확인한다.

Phytase의 효소 역가는 sodium phytate으로부터 phosphate이 분해되어 나오는 량을 측정하였다(Houde et al., 1990). 효소역가, 1 U는 pH 5.0 및 37°C 조건에서 1분 동안 기질로부터 분해되어 생성되는 1 µmol phosphate으로 정의하였다. 효소반응 혼합액은 0.1 M acetate(pH 5.0)에 0.2%(w/v) sodium phytate 농도의 기질용액 600 µl와 150 µl의 효소추출물을 혼합하여 준비하였고, 준비한 효소반응 용액은 37°C에서 30분 동안 배양하였다. 그리고 효소반응으로 생성된 phosphate의 함량을 측정하였다(Fiske and Subbarow, 1925).

Phytase의 역가 비교 및 효소 특성

발아보리 phytase의 역가를 다른 곡류와 비교하기 위하여 옥수수(Zea mays L. cv. Mibaek2nd), 밀(Triticum aestivum L. cv. Keumkang), 쌀(Oryza sativa L. cv. Odae) 및 콩(Glycine max L. cv. Daewon)을 지역 판매점을 통하여 구매하여 사용하였으며, 동일한 조건으로 25°C에서 4일간 발아 후 건조 하였다. 그리고 건조된 각 샘플은 분석 샘플 준비에서와 같이 분쇄, 추출 및 원심분리의 과정을 거쳐 상등액을 준비하여 phytase를 측정하고 효소 역가를 비교하였다.

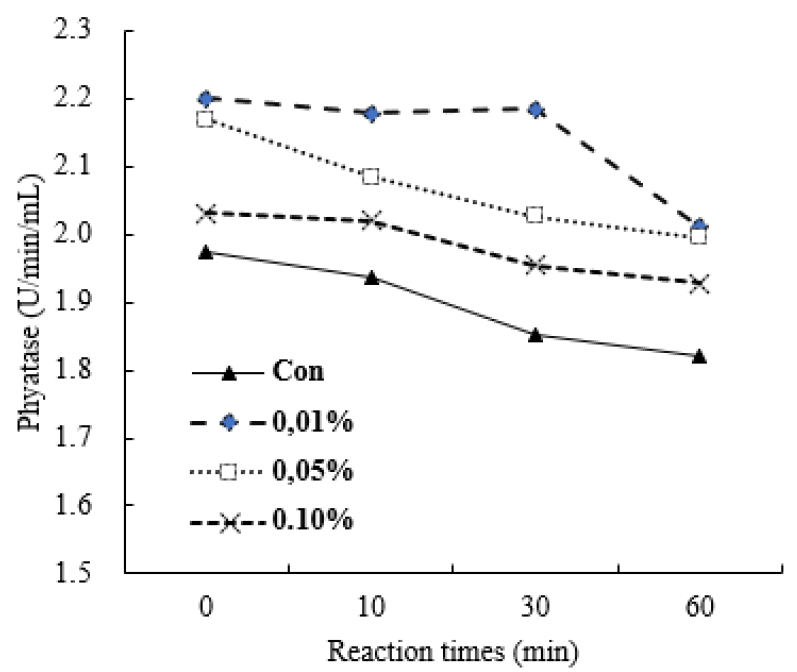

효소 특성 연구를 위한 발아보리 phytase의 활성 최적 온도는 35-65°C 범위에서 조사 하였고, phytase의 역가에 미치는 pH의 영향은 acetate buffer(pH 3.0-6.0) 및 Tris-acetic acid(pH 6.0-7.0)을 사용하여 측정하였다. 그리고 phytase 역가에 미치는 유화제의 영향은 효소반응 혼합액에 Tween 80을 0.01-0.1%(v/v)의 농도 범위로 첨가하여 조사하였다.

통계분석

본 실험에서 얻어진 자료에 대한 통계분석은 Statistical Package for the Social Sciences(SPSS, 2017)를 이용하였으며, 처리 평균치 간의 유의성 분석은 Duncan(1955)의 Multiple Range Test에 의거하여 5% 수준에서 검정하였다.

결과 및 고찰

발아 곡류의 phytase 역가 비교

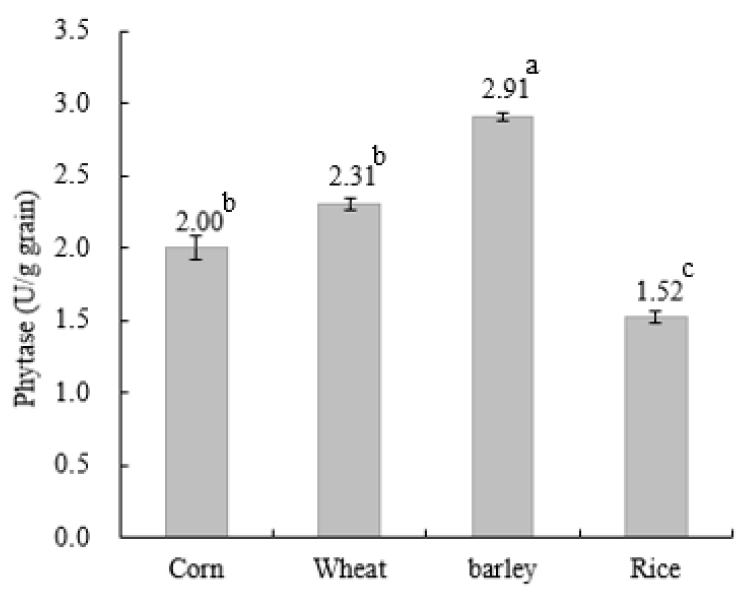

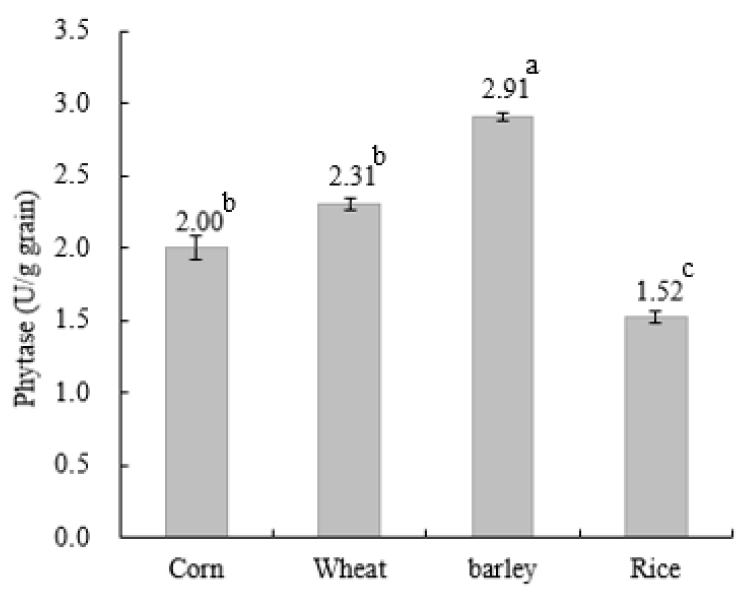

식물의 종자, 씨앗 및 곡류는 발아하는 동안에 phytate로부터 무기태 인을 생산하고, 이들 무기태 인은 식물의 성장을 위하여 사용된다. 그리고 씨앗은 발아를 통하여 자연적으로 phytase를 포함한 다양한 효소를 활성화한다. 본 연구에서도 Fig. 1에서와 같이 보리뿐만 아니라 옥수수, 밀 및 벼의 발아를 통하여 phytase가 다양하게 활성 됨을 확인하였다.

사료용 원료로 사용 가능하고 지역에서 구입하기 용이한 곡류로서 옥수수, 밀, 보리 및 벼를 동일한 조건에서 발아 후 phytase의 효소 역가를 측정하였을 때 곡류 종자 간에 명확히 다른 효소 활성을 나타내었다(Fig.1). 발아 후 보리의 phytase 역가는 2.91 ± 0.07 U/g으로 다른 곡류에 비하여 가장 높았다(p < 0.05). 발아 밀 및 옥수수의 phytase 역가는 각각 2.31 ± 0.08 및 2.00 ± 0.17 U/g으로 적은 차이를 나타내었으나, 발아 벼의 phytase 효소역가(1.52 ± 0.07 U/g)보다는 유의적으로 높았다(p < 0.05).

곡류의 발아는 조직 내 구조 및 기능의 변화와 밀접하게 연계되어 연속적으로 발생하는데 이러한 변화는 효소들의 활성에 의하여 이루진다(Duffus, 1987). Phytate는 성숙기에 빠르게 씨앗에 축적되며 총 인산의 60-90%를 차지한다(Greiner et al., 2000). 그리고 씨앗 내 phytate 함량 감소와 phosphate함량 증가는 발아하는 동안에 phytase 활성의 현격한 증가와 함께 발견되어 왔다(Laboure et al., 1993; Egli et al., 2002; Bouajila et al., 2020). Phytase는 대부분의 곡류에서 발견되며, 효소역가는 종자의 종류에 따라 매우 다양하다(Bartnik and Szafranska, 1987; Gupta et al., 2015; Vashishth et al., 2017). 동일한 조건에서 발아를 실시한 본 연구에서도 phytase의 활성이 곡류에 따라 다르게 나타남을 확인할 수 있었다(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of phytase activity between different germinated grains.

Eeckhout and De Paepe(1994)은 밀 및 호밀에서 phytase가 높았던 반면 보리에서는 좀 낮았고, 옥수수는 매우 낮은 활성을 보고하였다. 그리고 Azeke et al.(2011)의 연구에서도 밀에서 벼, 옥수수 및 수수 보다 phytase가 발아를 통하여 더 활성화 되었다. 다른 연구(Egli et al., 2002; Madsen and Brinch-Pedersen, 2019)에서도 밀과 보리가 옥수수 및 벼보다 더 높은 효소역가를 보였는데 본 연구의 결과와 유사한 경향이었다. 보리와 밀의 phytase에 대한 본 연구와는 다르게 보리보다 밀에서 더 높게 활성화됨을 보고하였다(Zimmermann et al., 2002; Delia et al., 2011). 그러나 Azeke et al.(2011)는 벼, 옥수수, 수수 및 밀에서 phytase가 0.41-0.67 U/g 수준으로 낮았음을 지적하였고, Steiner et al.(2007)는 귀리, 보리, 호밀 및 밀에서 0.4-6.0 U/g으로 품종 간에 phytase 활성에 큰 차이가 있음을 보고하였다.

보리의 발아 기간 동안 phytase의 변화

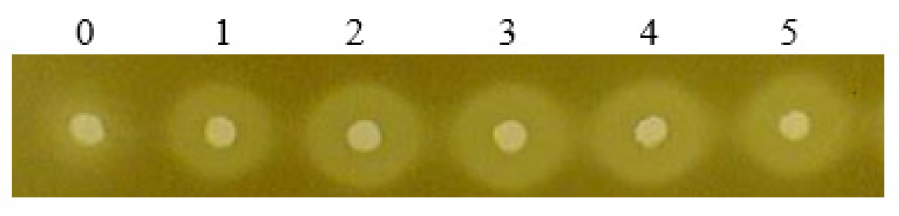

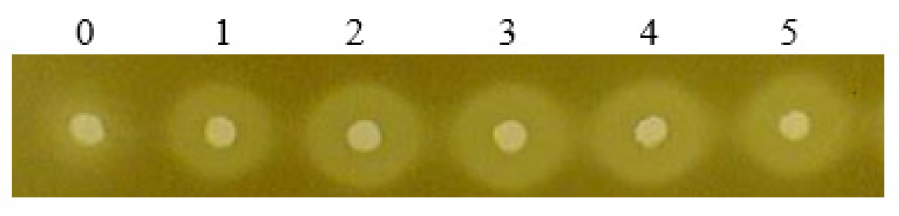

보리의 발효 기간 동안 phytase 발현을 스크린하기 위하여 Agar Plate Staining을 실시한 결과는 Fig. 2와 같다. 보리의 phytase의 발현은 효소 샘플을 채운 홀 주변의 효소 작용에 의한 밝은 환을 확인 할 수 있었으며, 발아 시작 0일차에서도 phytase 활성을 학인 할 수 있었다. 그리고 발아가 진행됨에 따라 효소활성 환의 크기도 확장 되었으며 더 선명한 밝은 환을 관찰 할 수 있었다. 발아 시작 0일차는 샘플 전처리 후 16시간 침지를 한 상태로 침지 기간에도 phytase의 효소 활성이 일어난 것으로 사료되며, 이러한 결과는 여러 품종의 보리를 4시간 30분 동안 침지 및 전 처리를 실시 후에 phytase 역가가 0.60-0.80 units/g dry matter의 수준에서 활성화됨이 보고된바 있다(Egli et al., 2002; Bouajila et al., 2020). 또한 본 연구의 효소 역가 측정에서도 0.43 U/g으로 효소 활성이 측정되었다(Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Plate screening of phytase during barley germination.

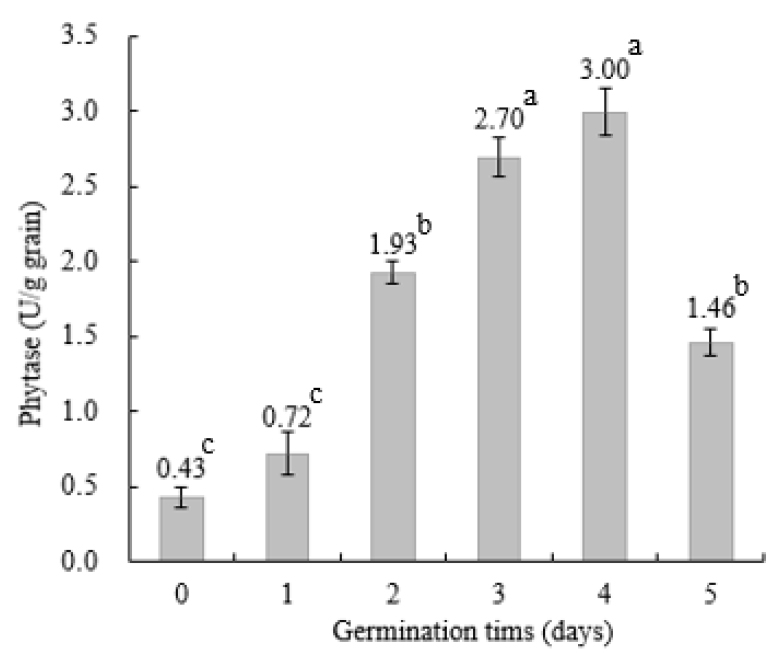

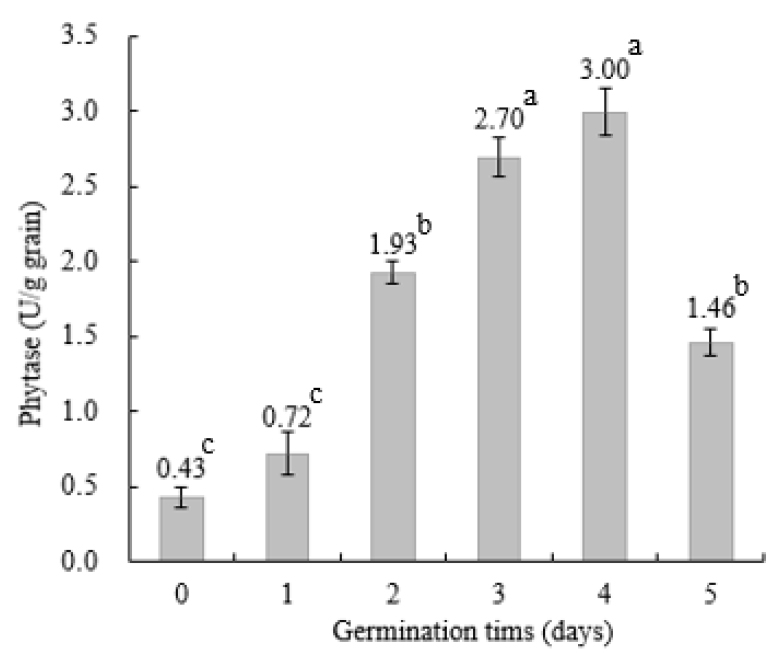

발아 기간 동안 보리의 phytase 역가 변화를 측정하였을 때 효소 역가의 변화를 Fig. 3과 같이 확인 할 수 있었다. 발아 기간 동안 효소의 역가는 발아 0 및 1일차에 각각 0.43 ± 0.14 및 0.72 ± 0.28 U/g 수준으로 소폭 증가하였고, 발아 2일차에는 1.93 ± 0.15 U/g으로 큰 폭으로 증가 하였다. 그리고 발아 3일차 이후 계속 증가하여 발아 4일차에 3.00 ± 0.32 U/g으로 최고 정점을 형성한 후에 발아 5일차에는 1.46 ± 0.18 U/g으로 감소하였다. 발화과정을 거치는 동안에 보리의 phytase 효소역가가 큰 폭으로 증가하는 것은 오랜 연구에서도 확인 할 수 있다(Bartnik and Szafranska, 1987; Lee, 1990). Azeke et al.(2011)은 여러 발아 곡류들에서 phytase의 할성이 3-16배로 증가하는 것을 보고하였고, 본 연구에서도 6.98배까지 증가하였다. 그리고 Bouajila et al.(2020)은 보리의 발아 실험에서 phytase 역가가 4.83-10.08배로 높아짐을 보고하였고, 발아 기간 중 4-5일차에 큰 폭으로 증가하여 12일차에 최고 정점을 형성함을 보고하였다. 이는 본 연구의 경향과는 다른 결과로 발효 환경의 차이에서 나타난 현상이라 사료된다. 또한 다른 연구(Ma and Shan, 2002; Azeke et al., 2011)에서도 발아 밀의 phytase 최고 활성이 발아 3일차 및 8일차에 형성됨이 보고된바 있다.

Fig. 3.

Developments of phytase by barley germination.

발아 보리 phytase의 특성

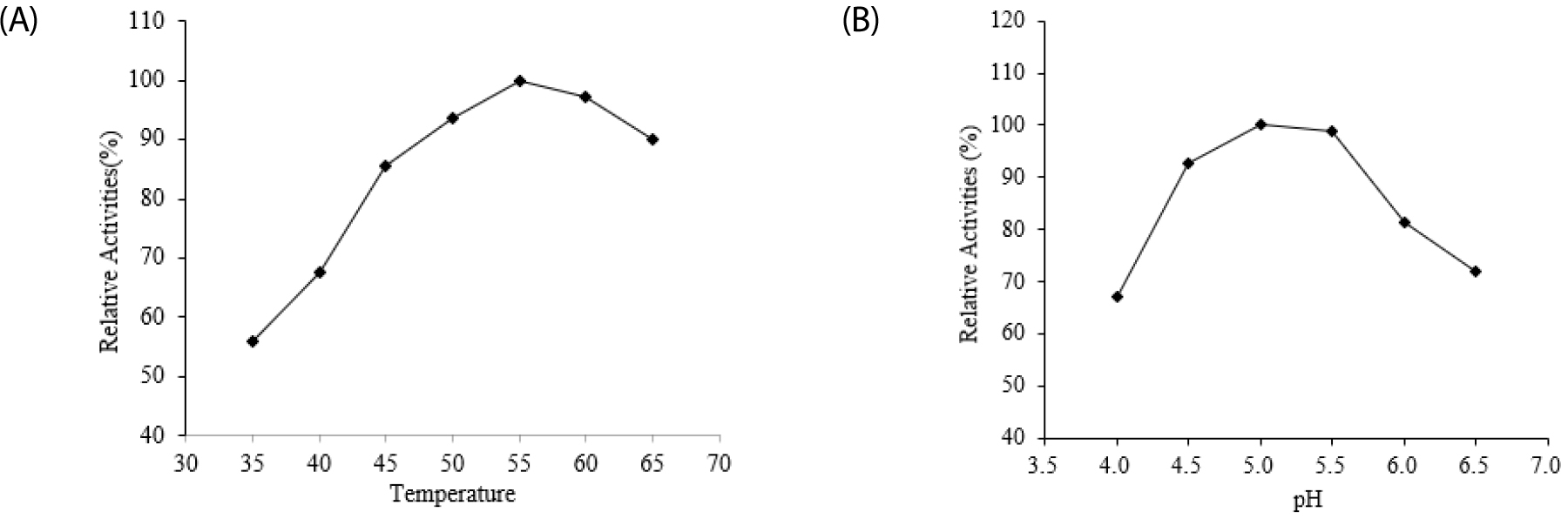

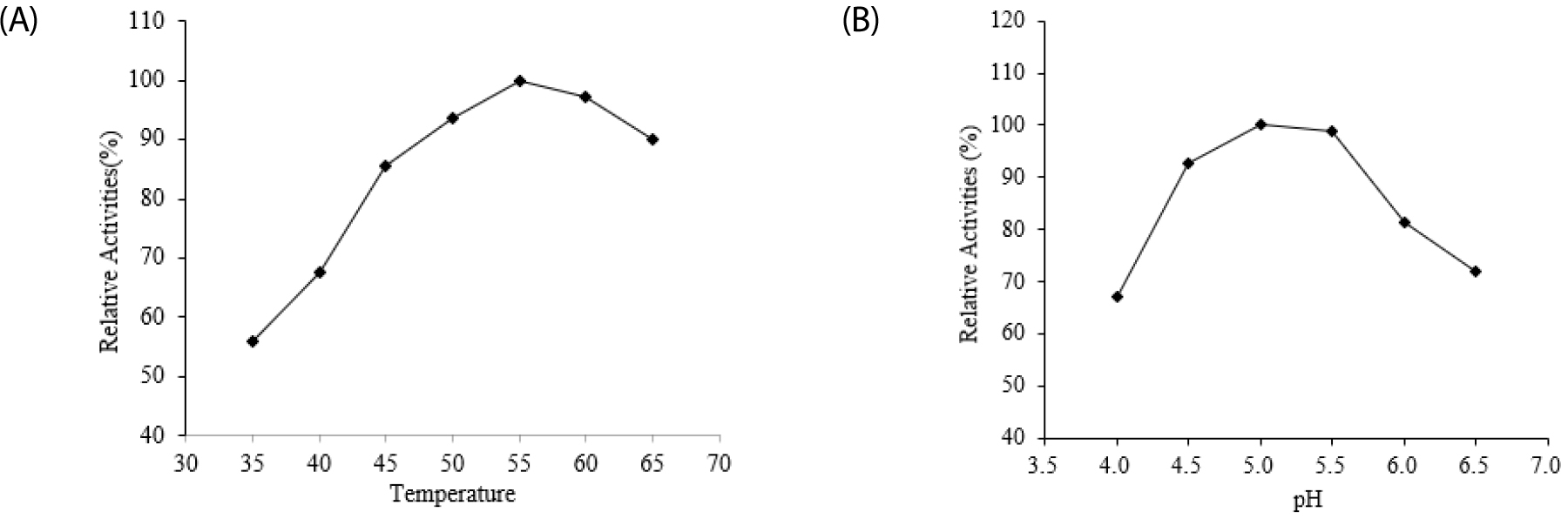

발아보리 phytase 활성의 최적 온도 및 pH는 Fig. 4에서와 같다. 발아보리의 phytase 활성에 미치는 온도를 35-65°C 범위에서 조사하였을 때 35°C에서 효소 역가가 가장 낮았으며, 온도가 증가함에 따라 점진적으로 증가하여 55°C에서 최고 정점을 나타내었다. 그리고 60 및 65°C에서는 점진 적으로 감소하였다(Fig. 4A). 발아보리의 phytase 활성에 미치는 pH를 4.0-6.5 범위에서 조사 하였을 때 pH 4.0에서 가장 낮은 역가를 나타내었고, pH가 증가함에 따라 phytase의 역가는 증가하여 pH 5.0에서 최고 정점을 나타내었다. 그리고 그 이후 pH가 증가함에 따라 감소하는 경향을 확인 하였다(Fig. 4B).

일반적으로 곡류와 콩에서 phytase의 최적 온도는 45-60°C 범위에서 형성되었고 최적 pH는 4.0-7.5 범위에서 나타나는 것으로 여러 연구에서 알 수 있다(Chang, 1967; Nagai and Funahashi, 1962; Yoshida et al., 1975; Chang et al., 1977; Mandal and Biswas, 1970). 또한 Brinch-Pedersen et al.(2014)의 연구에서 호밀, 밀, 벼, 귀리 및 보리의 phytase도 pH 4.6-6.0 및 38-55°C 범위에서 최적 효소활성을 나타내었다. 본 연구에서도 phytase 활성을 위한 최적 pH 및 온도가 이상의 연구 보고들의 범주 내에서 형성되었다(Fig. 4). 본 연구와 유사한 수준의 결과로 Greiner et al.(2000)은 발아보리에서 두 피크(P1, P2)의 phytase를 정제하였고 pH 5.0(P1) 및 pH 6.0(P2) 그리고 45°C(P1) 및 55°C(P2)에서 phytase의 최적 효소활성을 보고하였다. 그리고 Brinch-Pedersen et al.(2014)는 pH5.0 및 45°C에서 발아보리 phytase가 최적으로 활성화됨을 보고하였다.

Fig. 4.

Optimum temperature (A) and pH(B) of phytase.

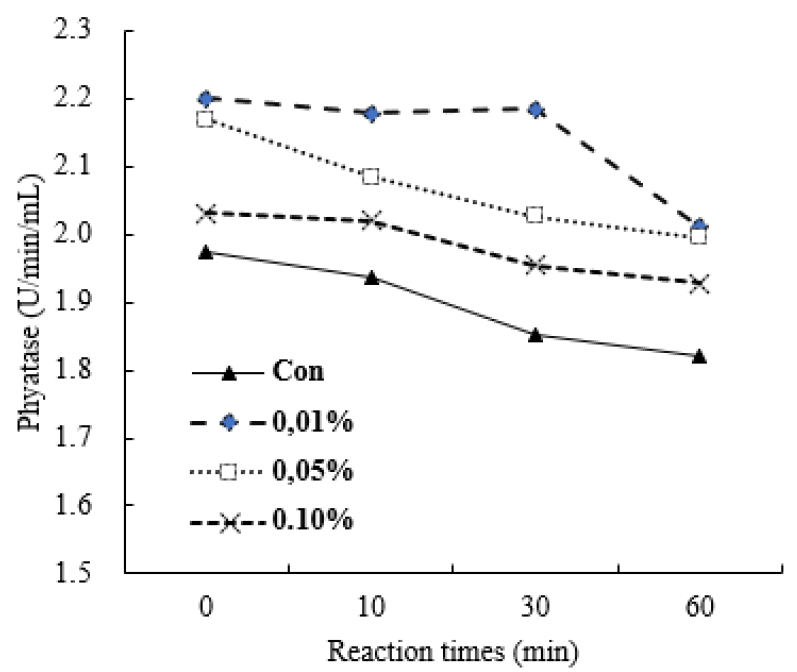

유화제가 발아보리의 phytase 활성에 미치는 영향은 Fig. 5와 같다. 유화제로서 Tween 80을 첨가하였을 때 무첨가에 비하여 phytase 활성이 증가하였다. 그리고 Tween 80을 효소 반응액의 0.01% 첨가하였을 때 다른 처리구보다 더 좋은 효과를 주었고, Tween 80 첨가량을 0.05 및 0.1%로 하였을 때 효소 역가가 낮아지는 현상을 나타 내었다. 그리고 모든 실험에서 반응시간이 경가함에 따라 초기 효소 역가에 비하여 낮아지는 경향을 보였으나, Tween 80을 0.01% 첨가한 처리구는 반응 시간 10 및 30분까지 유사한 수준을 유지하였다.

Fig. 5.

Effects of Tween 80 on phytase activity in the germinated barley.

유화제가 효소의 생성 및 역가에 미치는 영향에 대한 다양한 결과들이 보고되어 왔다(Han and Gallagher, 1987; Ebune et al., 1995; Lan et al., 2002). Tween 80과 sodium acetate이 A. ficcum NRRL 3135의 phytase를 증가시킨 반면, Triton X-100은 부정적 영향을 주었다(Ebune et al., 1995). 본 연구에서도 Tween 80 첨가로 무첨구의 1.03-1.18배 증가하였고, Han and Gallagher(1987)의 연구에서도 1.7배나 증가함을 보고하였다. 그러나 다른 연구에서는 Tween 80 및 Triton X-100의 영향을 발견하지 못하였다(Lan et al., 2002), 일반적으로 유화제가 효소에 긍정적 영향을 주는 경향이 있지만 효소의 유래 및 종류에 따라 다양한 효과가 나타나는 것으로 사료된다(Reese and Maguire, 1969).

Acknowledgements

본 연구는 기후변화 대응 지역순환형 Green New Deal(GND) 경축순환 연구단 구축을 위해 수행되었으며, 이 논문은 2021년 상지대학교 교내 연구비 지원에 의하여 수행되었으며, 이에 감사드립니다.

References

Azeke, M. A., Egielewa, S. J., Eigbogbo, M. U., Ihimire, I. G. (2011) Effect of germination on the phytase activity, phytate and total phosphorus contents of rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), millet (Panicum miliaceum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and wheat (Triticum aestivum). J Food Sci Technol 48:724-729.

10.1007/s13197-010-0186-y23572811PMC3551043Bartnik, M., Szafranska, I. (1987) Change in phytate content and phytase activity during germination of some cereal. Journal of Cereal Science 5:23-28.

10.1016/S0733-5210(87)80005-XBouajila, A., Ammar, H., Chahine, M., Khouja, M., Hamdi, Z., Khechini, J., Salem, A. Z. M., Ghorbel, A., Lopez, S. (2020) Changes in phytase activity, phosphorus and phytate contents during grain germination of barley (

Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars. Agroforest Syst 94:1151-1159.

10.1007/s10457-019-00443-yBrinch-Pedersen, H., Madsen, C. K., Holme, I. B., Dionisio, G. (2014) Increased understanding of the cereal phytase complement for better mineral bio-availability and resource management. J Cereal Sci 59:373-381.

10.1016/j.jcs.2013.10.003CAST (Council for Agricultural Science and Technology) (2002) Animal diet modification to decrease the potential for nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. Issue Paper 21:1-16.

Chang, C. W. (1967) Study of phytase and fluoride effects in germinating corn seeds. Cereal Chem 44:129.

Chang, R., Schwimmer, S., Burr, H. K. (1977) Phytate: Removal from whole dry beans by enzymatic hydrolysis and diffusion. J Food Sci 42:1098-1104.

10.1111/j.1365-2621.1977.tb12675.xCosgrove, D. J. (1966) The chemistry and biochemistry of inositol polyphosphates. Rev Pure Appl Chem 16:209-215.

Cowieson, A. J., Ruckebusch, J. P., Knap, I. (2016) Phytate-free nutrition: a new paradigm in monogastric animal production. Anim Feed Sci Technol 222:180-189.

10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.10.016Delia, E., Tafaj, M., Männer, K. (2011) Total Phosphorus, Phytate and Phytase Activity of Some Cereals Grown in Albania and used in Non-Ruminant Feed Rations. Biotechnol Biotechnol Eq 25:2587-2590.

10.5504/BBEQ.2011.0062Dersjant-Li, Y., Awati, A., Schulze, H., Partridge, G. (2015) Phytase in non-ruminant animal nutrition: a critical review on phytase activities in the gastrointestinal tract and influencing factors. J Sci Food Agric 95:878-896.

10.1002/jsfa.699825382707PMC4368368Duffus, C. M. (1987) Physiological aspects of enzymes during grain development and germination. In: Kruger J. E., Lineback D., Stauffer C. E. (eds) Enzymes and Their Role in Cereal Technology. American Association of Cereal Chemists inc USA pp 83-115.

Duncan, D. B. (1955) Multiple range and multiple F test. Biometrics 11:1-42.

10.2307/3001478Ebune, A., Al-Asheh, S., Duvnjak, Z. (1995) Effects of phosphate, surfactants and glucose on phytase production and hydrolysis of phytic acid in canola meal by

Aspergillus ficuum during solid-state fermentation. Bioresource Technology 53:7-12.

10.1016/0960-8524(95)00041-CEeckhout, W., De Paepe, M. (1994) Total phosphorus, phytatephosphorus and phytase in plant feedstuffs. Anim Feed Sci Technol 47:19-29.

10.1016/0377-8401(94)90156-2Egli, I., Daavidsson, L., Juillerat, M. A., Barclay, D., Hurrell, R. F. (2002) The Influence of soaking and germination on the phytase activity and phytic acid content of grains and seeds potentially useful for complementary feeding. J Foof Sci 67:3484-3488.

10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb09609.xFiske, C. H., Subbarow, Y. (1925) The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J Biol Chem 66:375-400.

10.1016/S0021-9258(18)84756-1Furrer, O. J., Stauffer, W. (1987) P-Verlagerung im Boden und Auswaschung. In: FAC Oktobertagung 1987: Phosphat in Landwirtschaft und Umwelt, Eidgenössische Forschungsanstalt für Agrikulturchemie und Umwelthygiene. FAC, Liebefeld- Bern, pp 83-90.

Gibson, D. (1987) Production of extracellular phytase from Aspergillus ficuum on starch media. Biotechnol Lett 9:305-310.

10.1007/BF01025793Greiner, R., Jany, K. D., Alminger, L. (2000) Identification and properties of

myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases (phytases) from barley (

Hordeum vulgare). J Cereal Sci 31:127-139.

10.1006/jcrs.1999.0254Greiner, R., Konietzny, U., Jany, K. D. (1998) Purification and properties of a phytase from rye. J Food Biochem 22:143-161.

10.1111/j.1745-4514.1998.tb00236.xGupta, R. K., Gangoliya, S. S., Singh, N. K. (2015) Reduction of phytic acid and enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients in food grains. J Food Sci Technol 52:676-684.

10.1007/s13197-013-0978-y25694676PMC4325021Haefner, S., Anja Knietsch, A., Scholten, E., Braun, J., Lohscheidt, M., Zelder, O. (2005) Biotechnological production and applications of phytases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 68:588-597.

10.1007/s00253-005-0005-y16041577Hamada, J. S. (1996) Isolation and identification of the multiple forms of soybean phytases. J Am Oil Chem Soc 73:1143-1151.

10.1007/BF02523376Han, Y. W., Gallagher, D. J. (1987) Phosphatase production by Aspergillus ficuum. Journal of Indian Microbiology 1:295-301.

10.1007/BF01569307Harland, B. F., Oberleas, D. (1999) Phytic acid complex in feed ingredients. In: Coelho MB, Kornegay ET (eds) Phytase in animal nutrition and waste management, 2nd rev edn. BASF, Mexico, pp 69-76.

Hayakawa, T., Toma, Y., Igaue, I. (1989) Purification and characterization of acid phosphatases with or without phytase activity from rice bran. Agric Biol Chem 53:1475-1483.

10.1080/00021369.1989.10869506Houde, R. L., Alli, I., Kermasha, S. (1990) Purification and character- ization of canola seed (Brassica sp.) phytase. J Food Biochem 14:331-351.

10.1111/j.1745-4514.1990.tb00846.xHuebel, F., Beck, E. (1996) Maize root phytase. Purification, charac- terization, and localization of enzyme activity and its putative substrate. Plant Physiol 112:1429-1436.

10.1104/pp.112.4.142912226456PMC158074Humer, E., Schwarz, C., Schedle, K. (2015) Phytate in pig and poultry nutrition. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr 99:605-625.

10.1111/jpn.1225825405653Konietzny, U., Greiner, R., Jany, K. D. (1995) Purification and characterization of a phytase from spelt. J Food Biochem 18:165-183.

10.1111/j.1745-4514.1994.tb00495.xKumar, V., Sinha, A. K., Makkar, H. P. S., Becker, K. (2010) Dietary roles of phytate and phytase in human nutrition: a review. Food Chem 120:945-959.

10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.052Laboure, A. M., Gagnon, J., Lescure, A. M. (1993) Purification and characterization of a phytase (myo- inositolhexakisphosphate phosphohydrolase) accumulated in maize (Zea mays) seedlings during germination. Biochemistry Journal 295:413-419.

10.1042/bj29504138240238PMC1134897Lan, G. Q., Abdullah, N., Jalaludin, S., Ho, Y. W. (2002) Culture conditions influencing phytase production of

Mitsuokella jalaludinii, a new bacterial species from the rumen of cattle. J Applied Microbiology 93:668-674.

10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01727.x12234350Lee, W. (1990) Phytic acid content and phytase activity of barley malt. J Am Soc Brew Chem 48:62-65.

10.1094/ASBCJ-48-0062Ma, T. N., Blaabjerg, K., Labouriau, R., Poulsen, H. D. (2015) High moisture airtight storage of barley and triticale: effect of moisture level and grain processing on nitrogen and phosphorus solubility. Anim Feed Sci Technol 210:125-137.

10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.09.017Ma, X., Shan, A. (2002) Effect of germination and heating on phytase activity in cereal seeds. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci 7:1036-1039.

10.5713/ajas.2002.1036Madsen, C. M., Brinch-Pedersen, H. (2019) Molecular Advances on phytases in barley and wheat. Int J Mo Sci 20:2459-2469.

10.3390/ijms2010245931109025PMC6566229Mandal, N. C., Biswas, B. B. (1970) Metabolism of inositol phosphates. I. Phytase synthesis during germination in cotyledons of mung beans, Phaseolus aureus. Plant Physiol 45:4-7.

10.1104/pp.45.1.416657276PMC396344McCollum, E. V., Hart, B. (1908) On the occurrence of a phytin splitting enzyme in animal tissue. J Biol Chem 4:497-500.Nagai, Y., Funahashi, S. (1962) Phytase (myo-inositol hexaphosphate phosphohydrolase) from what bran. Part I. Purification and subtrate specificity. Agric Biol Chem 26:794-803.

10.1080/00021369.1962.10858050Nahm, K. H. (2002) Efficient feed nutrient utilization to reduce pollutants in poultry and swine manure. Crit Rev Environ products as influenced by harvest year and cultivar. Anim Feed Sci Technol 133:320-334.

Nakano, T., Joh, T., Tokumoto, E., Hayakawa, T. (1999) Purification and characterization of phytase from bran of Triticum aestivum L. Cv. Nourin #61. Food Sci Technol Res 5:18-23.

10.3136/fstr.5.18Raboy, V. (2003) Myo-inositol-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexakisphosphate. Phytochemistry 64:1033-1043.

10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00446-1Rao, D. E. C. S., Rao, K. V., Reddy, T. P., Reddy, V. D. (2009) Molecular characterization, physicochemical properties, known and potential applications of phytases: an overview. Crit Rev Biotechnol 29:182-198.

10.1080/0738855090291957119514894Rapoport, S., Leva, E., Guest, G. M. (1941) Phytase in plasma and erythrocytes of vertebrates. J Biol Chem 139: 621-632.

10.1016/S0021-9258(18)72935-9Reese, E. T., Maguire, A., (1969) Surfactants for enzyme production by microorganisms. Appl Microbiol 17:242-245.

10.1128/am.17.2.242-245.19695813298PMC377657Sebastian, S., Touchburn, S. P., Chavez, E. R. (1998) Implications of phytic acid and supplemental microbial phytase in poultry nutrition: a review. World's Poult Sci J 54:27-47.

10.1079/WPS19980003SPSS (2017) Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. IBM® SPSS® Statistics 25.0, IBM Now York USA.

Steiner, T., Mosenthin, R., Zimmermann, B. (2007) Distribution of phytase activity, total phosphorus and phytate phosphorus in legume seeds, cereals and cereal by-products as influenced by harvest year and cultivar. Anim Feed Sci Technol 133:320-334.

10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2006.04.007Sung, H. G., Shin, H. T., Ha, J. K., Lee, J. H. (2005) Effect of germination temperature on characteristics of phytase production from barley. Bioresour Technol 96:1297-1303.

10.1016/j.biortech.2004.10.01015734318Vashishth, A,, Ram, S,, Beniwal, V. (2017) Cereal phytases and their importance in improvement of micronutrients bioavailability. Biotech 7:42.

10.1007/s13205-017-0698-528444586PMC5428090Wu, P., Tian, J. C., Walker, C. E., Wang, F. C. (2009) Determination of phytic acid in cereals-a brief review. Int J Food Sci Technol 44:1671-1676.

10.1111/j.1365-2621.2009.01991.xYoshida, T., Tanaka, K., Kasai, Z. (1975) Phytase activity associated with isolated aleurone particles of rice grains. Agric Biol Chem 39:289-290.

10.1080/00021369.1975.10861594Zimmermann, B., Lantzsch, H. J., Langbein, U., Drochner, W. (2002) Determination of phytase activity in cereal grains by direct incubation. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr 86:347-352.

10.1046/j.1439-0396.2002.00393.x12452977